Indigenous Identity

Although the regulations have changed from blood quantum to more complex determinations of belonging, Indigenous Peoples are still the only people where the Government of Canada decides who belongs and who doesn’t.

“Pretendians” are now being uncovered by the media, and these determinations are complicated and controversial, shaped by colonialism and a long history of government regulation and oppression. For many, identity is something that was lost and is now being reclaimed. It is both internal to an individual and external through community recognition. And it is a key factor in understanding oneself in relation to land, community, and spirit. For students, it goes far beyond ticking a box on an admissions form or scholarship application. Based on the desire to understand what Indigenous identity means to students themselves, a research team from BU’s Indigenous Peoples’ Centre and CARES Research Centre led students at both high school and post-secondary levels to create photography and films in response to the question, “What does Indigenous identity mean to you?”

Listen to facilitator and contributor Ayden Lambert talk about this exhibition on CBC Radio Noon:

Co-Researchers and Artists:

Alison Downing

Ayden Lambert

Brittany Knight

Chloe McKay

Ethan Laugher

Grant Maluga

Julia Stoneman Sinclair

Karleen Anderson

Krystine Mousseau

Sary Innerst

Steph Spence

Tara Roulette

Tori Sinclair

Snowshoes by Alison Downing. These traditional snowshoes (wood and rawhide) given to my husband by his dad, represent the journeys that many Indigenous People have taken away from their home communities, families, and traditional lands. This picture is dedicated to my father-in-law who passed away in 2024.

Moccasins by Alison Downing. As a mom, my children have profoundly shaped the person I am today. My journey as a parent includes providing opportunities for my children to better understand and connect to their Indigenous identities (Red River Métis and Ojibway).

Infinity Pin / Sash by Alison Downing. The arrowhead sash and blue infinity flag are the most commonly recognized symbols of the Red River Métis People. These symbols represent the distinct culture, history, language, and traditions of the Red River Métis People. The sash and pin were crafted by Alison Downing.

Sash in Tree by Alison Downing. The picture of the brightly coloured Red River Métis sash surrounding the branch of a sick and dying tree represents the importance of honouring and incorporating Indigenous knowledge systems and ways of being to help heal the land which has become harmed as a result of Industrial society.

IPC by Ayden Lambert. When thinking of what sort of photograph and what subject would best represent how I connect with indigenous culture, I thought that the Indigenous Peoples Centre (IPC) at Brandon University would be perfect. It means a lot to me that the school has this space for students who come from an Indigenous background to connect with one another and form a community on campus which is conducive to expressions of Indigeneity within the larger academic structure of BU. Many of the participants within this photovoice project have come from this community and so this picture also serves as a bit of a tribute to them as well.

Fire by Ayden Lambert. When reflecting upon this photograph, the flame became a representation of the collective spirit of the Indigenous and Métis peoples of Manitoba, who despite processes of westernization and colonization, still keep the flame of our culture and backgrounds burning strong. When I viewed this image with that perspective in mind, it suddenly became very powerful to me and relevant to the battle that is waged everyday for the first peoples of this area to both have a voice and remain true to their ways.

Sunset Photos by Ayden Lambert. I love these dual photos for how the hues of red and yellow contrast against the black in a manner which to me was evocative of The Medicine Wheel’s most recognizable shades. Perhaps photography’s greatest strength is the capacity it has to provide meaning within the context of a single captured image and how any number of people can interpret that meaning in any number of ways. For me, it was rewarding to be able to put meaning into these photos by way of that initial connection I made between the colours of the sunset and some of the most important symbology for indigenous peoples.

Sunset Photos by Ayden Lambert. I love these dual photos for how the hues of red and yellow contrast against the black in a manner which to me was evocative of The Medicine Wheel’s most recognizable shades. Perhaps photography’s greatest strength is the capacity it has to provide meaning within the context of a single captured image and how any number of people can interpret that meaning in any number of ways. For me, it was rewarding to be able to put meaning into these photos by way of that initial connection I made between the colours of the sunset and some of the most important symbology for indigenous peoples.

Two Worlds by Brittany Knight. This photo was taken in two locations, each representing a different part of where I have lived. On the left side, it showcases a lake to represent my life in Northern Manitoba. The right side depicts a street to highlight my life in the city. In the centre, I am standing in the middle of both locations. This is to highlight that no matter where I am, I am still me despite my location.

Traumas by Brittany Knight. As Indigenous people, I feel that many of us have trouble with some sort of trauma, whether it's our own or intergenerational. Sadly, many people turn towards alcohol as a form of coping. I wanted to use an empty alcohol bottle to represent a person who is battling with alcoholism. The bottle is empty, beaten up, the label is not complete, this is to represent what alcohol can do to a person. The bottle is discarded along the road, left, forgotten, to represent what society makes of people battling alcoholism.

Struggles by Brittany Knight. Many Indigenous people battle with alcoholism, but many people also go through the struggle of getting sober. I wanted to showcase someone clawing their way out of their battle with alcoholism. If I had better skills using photoshop, I would have showed a whole person stuck in a bottle with them climbing out, but I lack the skills. The person that is stuck in the bottle will need to squeeze through the neck of the bottle, which will not be an easy task, as they will be uncomfortable and may need to lose apart of themselves (alcohol/trauma) to get out. The picture may seem blurry, but I wanted to focus on the hand rather than the bottle of alcohol, as we need to focus on the person getting sober rather than their past behaviour/misdeeds. I also waited for a clear day to take this photo, as I wanted the person reaching up towards the clear sky/sunlight, to represent the person clearing their own mind and realizing they need to get sober. I also chose this location to highlight the fact that even if the person makes it out of the bottle, that there will still be struggles, the walls boxing them in, outside of bottle but you will still have more space and freedom compared to being in the bottle.

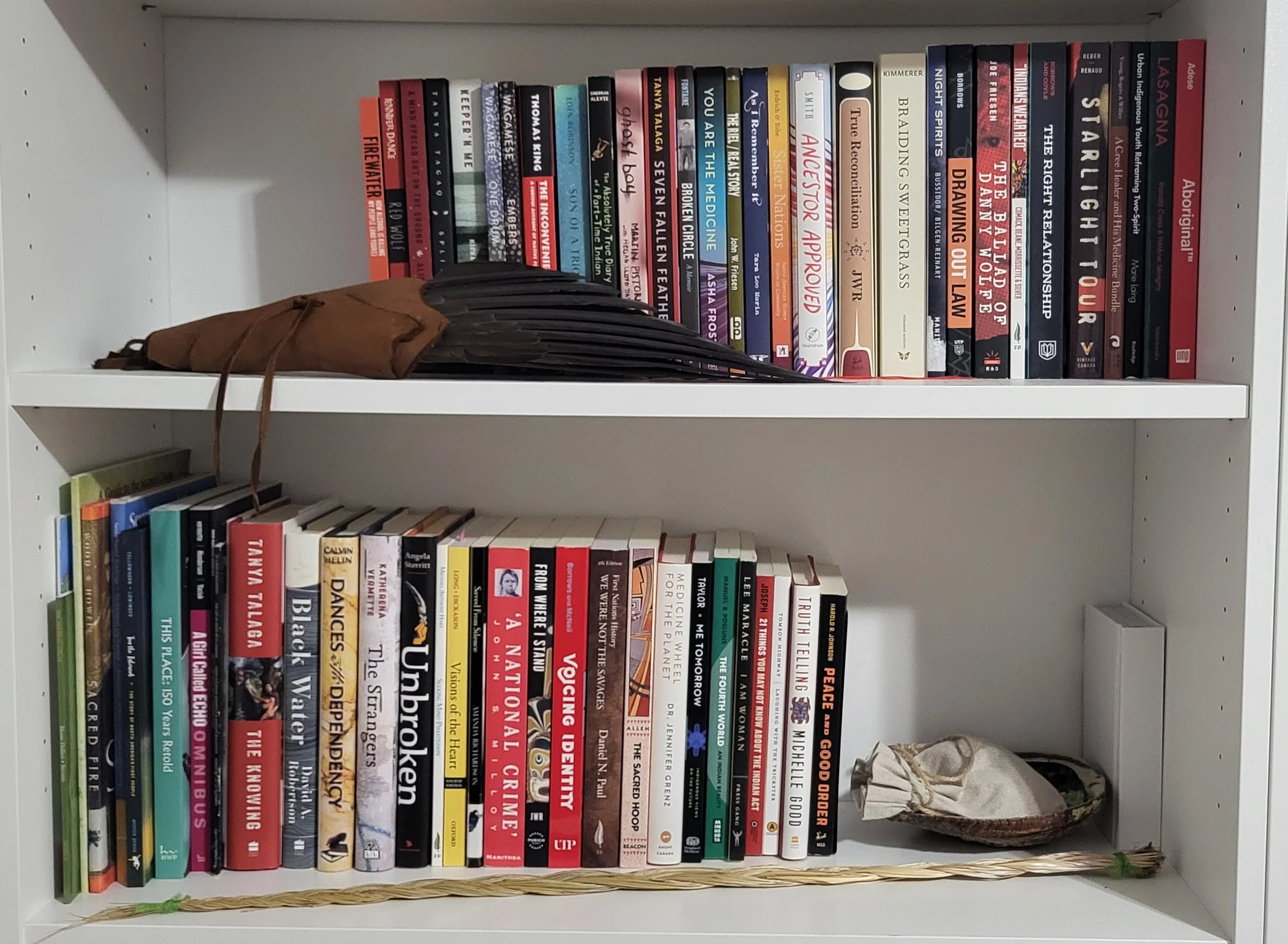

Reconnection by Brittany Knight. I took a photo of my book shelf, where I have books on different Indigenous subjects/perspectives. On my shelf, I also have some traditional medicine, along with a goose wing I received from an elder to help smudge. If you do not live in your community, you may not have access to knowledge that elders may possess. As I do not have access to my elders, due to distance between us or them passing on, I collect as many books as I can to help widen my knowledge.

By Chloe McKay

By Ethen Laugher

By Ethen Laugher

By Ethen Laugher

By Ethen Laugher

By Ethen Laugher

By Ethen Laugher

By Grant Maluga. As a child I wasn’t raised on the Rez but I was always visiting. My parents separated and I grew up in a “white man’s world” living with my dad. I never really started figuring out my indigenous identity till around 2011-2012. Around in 2013 I attended my first sweat as well as my first vision quest between that time and 2014 I got my spirit name “Aazhaawashkoini Makwa” which translates to Blue Spirit Bear”. This started me on my Identity journey which I am still on today.

By Grant Maluga. What is Identity to me? Well, I’m still trying to figure that out. Growing up I was just “winging it” I didn’t really have any role models growing up and you can say that I grew up in a bubble. Surprisingly , even though I grew up in Brandon. As I got older and moved onto high school, I decided to join football and then rugby. During my time playing sports I learned a lot about myself and was able to find my Identity. At first it took people around me to encourage me to play as it would help me in many ways such as building my confidence, I felt like I had purpose, at the time I felt like I was able to find myself and grow into the person that I needed to be and I am proud of today. This is a picture of me at the Crocus Plains Football Field. This is where I spent much of my time when in highschool and learned a lot about myself and life on this field.

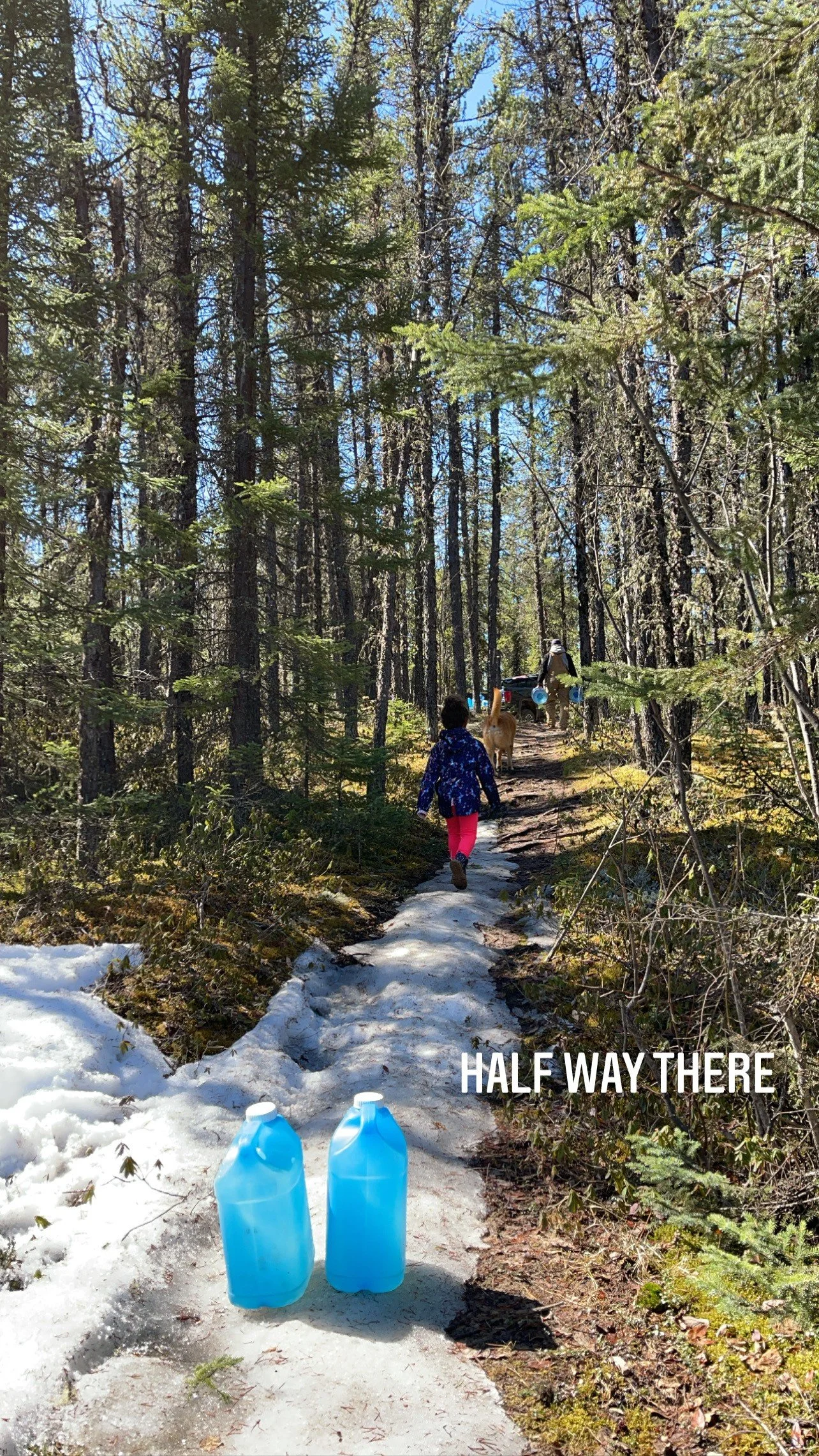

ᓰᐲᓯᓵᐳᕀ sîpîsisâpoy Creek By Julia Stoneman Sinclair Growing up, I was taught that women carry the responsibility of being water carriers/protectors. I had an inherent connection with water before I knew I held this responsibility as a woman and mother. Growing up in the North, I was surrounded by water my entire life. I walked out of my house and was welcomed to the sights, smells, and sounds of the lake close to us. The loons were always singing, moose would roam on the shore, and food was abundant in the gift of fish that the lake gave us. I have sat beside the water in times of great sorrow and grieving and at times of celebration and happiness. It has always been there to care for its people. This picture shows that, unfortunately, Mother Earth is affected by human activity across Turtle Island and the world. Lynn Lake was a mining town, and we have been under a boil water advisory for the majority of my life. The water isn’t clean to drink or sometimes even bathe in. The day we took this picture, we went to a creek out of Lynn Lake and filled water jugs for four households as the only clean water filter at the Northern had been broken for a few days. This was the only way to have clean water. Humans have damaged this land, but it still provides ways to care for us, like this spring of free, clean water for the community to drink. It's only making sure you have the means to get there and haul the water.

Nanâtawihowin (ᓇᓈᑕᐃᐧᐦᐅᐃᐧᐣ) medicine By Julia Stoneman Sinclair When introducing myself I am always proud to share that I come from the water and the land of northern Manitoba. Growing up in the north can be very hard, but to me, it is all worth it. I find beauty, love and medicine everywhere I look when I am home. The warm air off of the lake, the birds singing every morning, the wolves howling at night, to me I see and feel a love song from Mother Earth to her children. The land is covered in medicine, softness and sweet smells everywhere you walk. This picture was taken at Cockeram Lake just outside of Lynn Lake, Manitoba where I grew up. My brother had taken my daughters, our dog Nova and myself out for a day of fishing and a shore lunch of fish, beans and potatoes. I was walking along the land right beside the beach where we landed the boat and felt the need to take a photo and remember the soft and sweet smelling land we were visiting for the afternoon.

Cree Matriarchy by Karleen Anderson. Here we see a group of women playing bingo with their friends. But when you look closer within, you see Indigenous women that hold powerful roles within our societies. They are grandmothers, mother's and aunts to everyone in our community and they are the women that hold our community together.

Tataskweyak Northern Beauty, by Karleen Anderson. Taken on Odei River bridge on provincial road 280 in Northern Manitoba. Here in the south, we do not know much about northern Manitoba due to the isolation. But here is my community where I grew from a young child, there is hidden beauty all over the North and this picture represents that beauty.

Northern Lights by Karleen Anderson. Here in Brandon, we rarely see the Northern Lights due to light pollution within our area. In Split Lake, the northern lights are always bright and beautiful as you see in the picture. This picture represents of the beauty of my northern community. We just see the beauty of Mother Nature which are interpersonal to Indigenous livelihood.

Anderson-Keeper Family, by Karleen Anderson. Here is the source of my identity, my family. They are the people that modeled my life and continue to represent where I came from. My family is what taught me how to be proud of being an Indigenous woman and I always hold that feeling close.

By Krystine Mousseau

By Krystine Mousseau

Cedar by Krystine Mousseau. This is a photo of cedar. Cedar is used in Indigenous cultures for many different purposes such as making tea.

Identity by Sary Innerst. It took me along time to figure out what identity meant. For the longest time I thought it meant fitting in to a specific group and I never did. Adopted from Saulteaux /Cree/ Irish / Scottish people, Raised by American Anglo Saxon/ Irish/ German people. Then living in the foster system, I never seemed to fit in. I was an addict and drinker and fighter for years to try to find myself. It was only when I began to sober up and look inside myself and heal that I found out who I was. I AM a creation from the Great unknown. Finding a connection to Creator gave me a sense of identity; not in churches or ceremonies but in those quiet moments where I knew I was a part of something bigger. My identity is being a spirit in this body with Creator guiding and helping me in all I do, a grandmother, a mother, a sister, an auntie,a friend, a doctor, a coach, a taxi driver, a laborer , a chef, an entrepreneur, an advocate. All of this is through Great Spirit, connected to all of creation here on this mighty earth. That is my identity; it's all about connection.

By Sary Innerst. The picture of the horses was one of my favorite moments; I was searching for answers and went for a drive. All of a sudden, four horses, the color of the medicine wheel came into the field. It was a confirmation of my connection with God. I love those moments!

By Sary Innerst. The picture with the sandcastle, was a moment when I was dedicated to healing the child within. We had fun building a sandcastle. Once I let little me play and have fun, I became more connected inside myself.

By Steph Spence

By Steph Spence

By Steph Spence

No matter where you go in life and where you travel to, or what career you’ll have, being Indigenous in any colonial environment, you will always walk on land that is rightfully yours, today, tomorrow and forevermore” - By Tara Roulette.

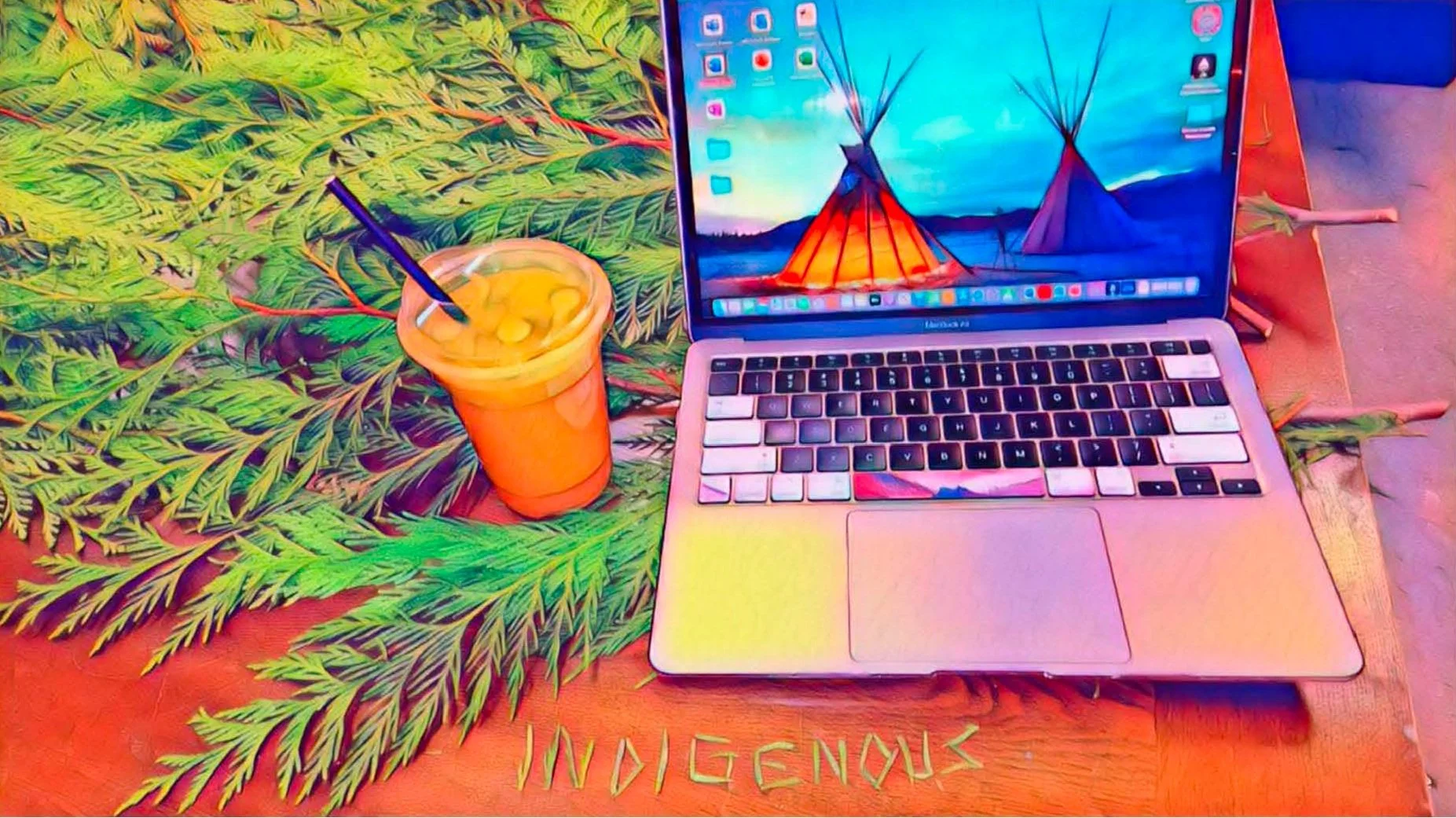

By Tara Roulette. As an Indigenous student in university, I navigate a system built on colonial foundations where my identity, history, and ways of knowing are often marginalized. But despite all these difficult challenges, I am committed to reclaiming space, advocating for indigenous perspectives, and challenging the expectations imposed on me. My academic journey is not just about earning a degree, it's about decolonizing education, amplifying indigenous voices, And ensuring that future generations don't have to fight the same battles. I refuse to conform to the structures designed to erase my culture and instead strive to transform them from within. Whether through activism, community engagement or even my studies, I am determined to dismantle the barriers that seek to silence Indigenous resilience.

By Tara Roulette. eing in school and pursuing my education of becoming a lawyer, I am committed to this path because my people deserve justice. They deserve a legal system that respects them, not one that works against them. And if I can be a part of making that happen, even if it's in small or big ways, every struggle along the way will be worth it. I think about the land that has been taken, the treaties that have been ignored, and the families torn apart by legal systems that were never designed with us in mind. I also think about the resilience of my people, how despite centuries of injustice, we continue to fight for our sovereignty, our traditions, and our future. The career that I chose in becoming a lawyer, I can be part of that fight, using my knowledge to empower my people and challenge the laws that have historically harmed us.

What This Photo Means to Me by Tara Roulette. Being Indigenous as a university student in the colonial world is a constant negotiation of space, identity, and survival. It means walking through institutions built on stolen land, where the architecture, curriculum and traditions often erase or commodify your existence. It means seeing indigenous knowledge sidelined as “alternative” well western frameworks are treated as the “normal”. It means professors and peers questioning your intelligence, your legitimacy, your very presence in the room. It's carrying the weight of your ancestors while being expected to assimilate. It's being asked, “what percentage are you?” Or being told, “you don't look native”. It's the loneliness of being the only one in your class, or one of a handful in your entire program. It's the deep frustration of watching institutions perform land “acknowledgements” but refused to divest from extractive industries that harm indigenous lands and communities. At the same time, it's also an act of resistance. Every paper written, every degree earned, every moment spent reclaiming your language, culture and in history within these spaces which is a disruption to colonial expectations. It's finding kinship with other indigenous students, creating community where the institution fails to provide one. It's carrying forward the knowledge of those who fought for you to be here, knowing you are not just surviving but laying the groundwork for future generations. Being indigenous to me in university is exhausting, infuriating and isolating… but it is also very powerful, because it is proof that despite everything, we are still here, thriving and beating all the odds.

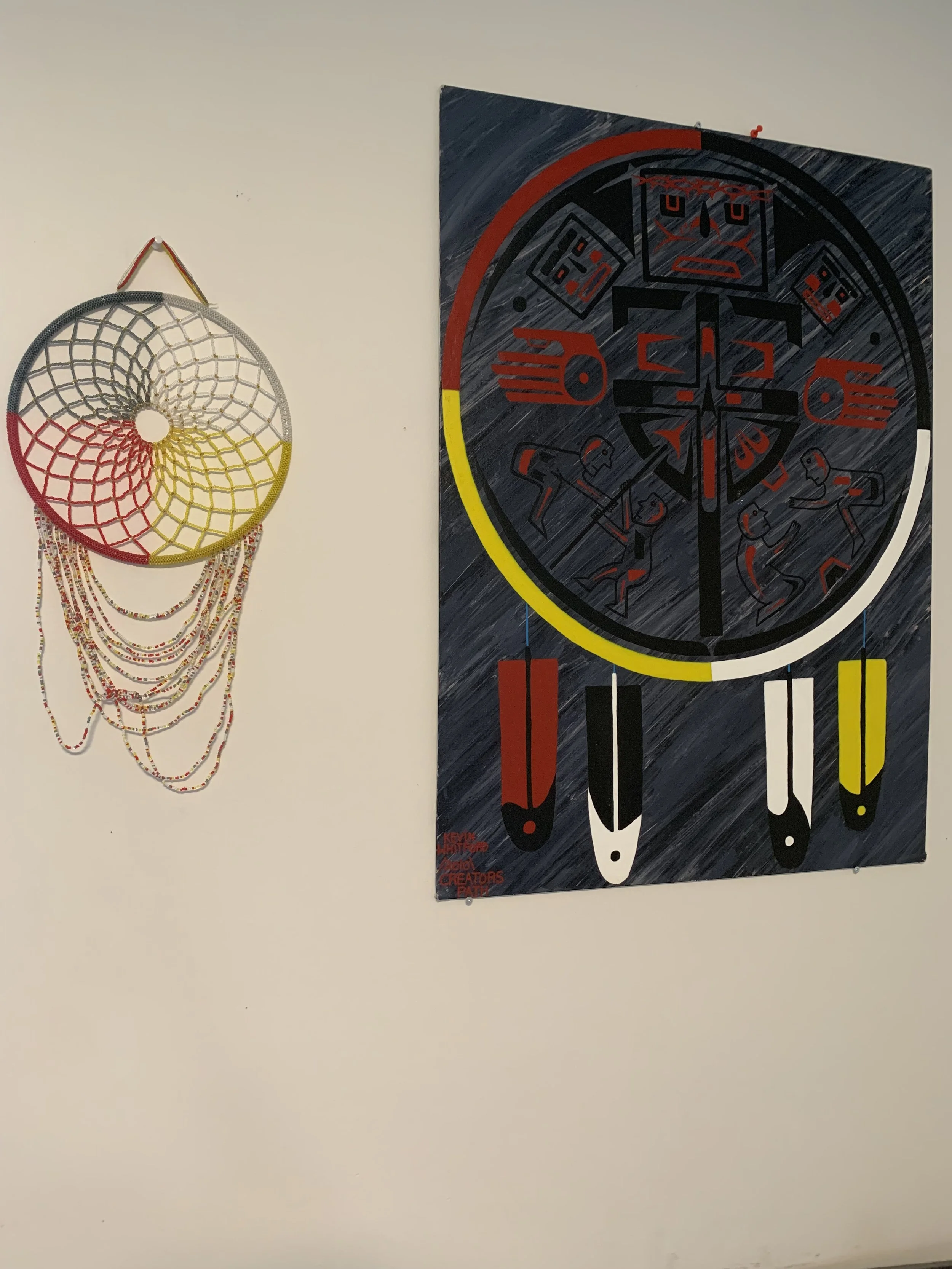

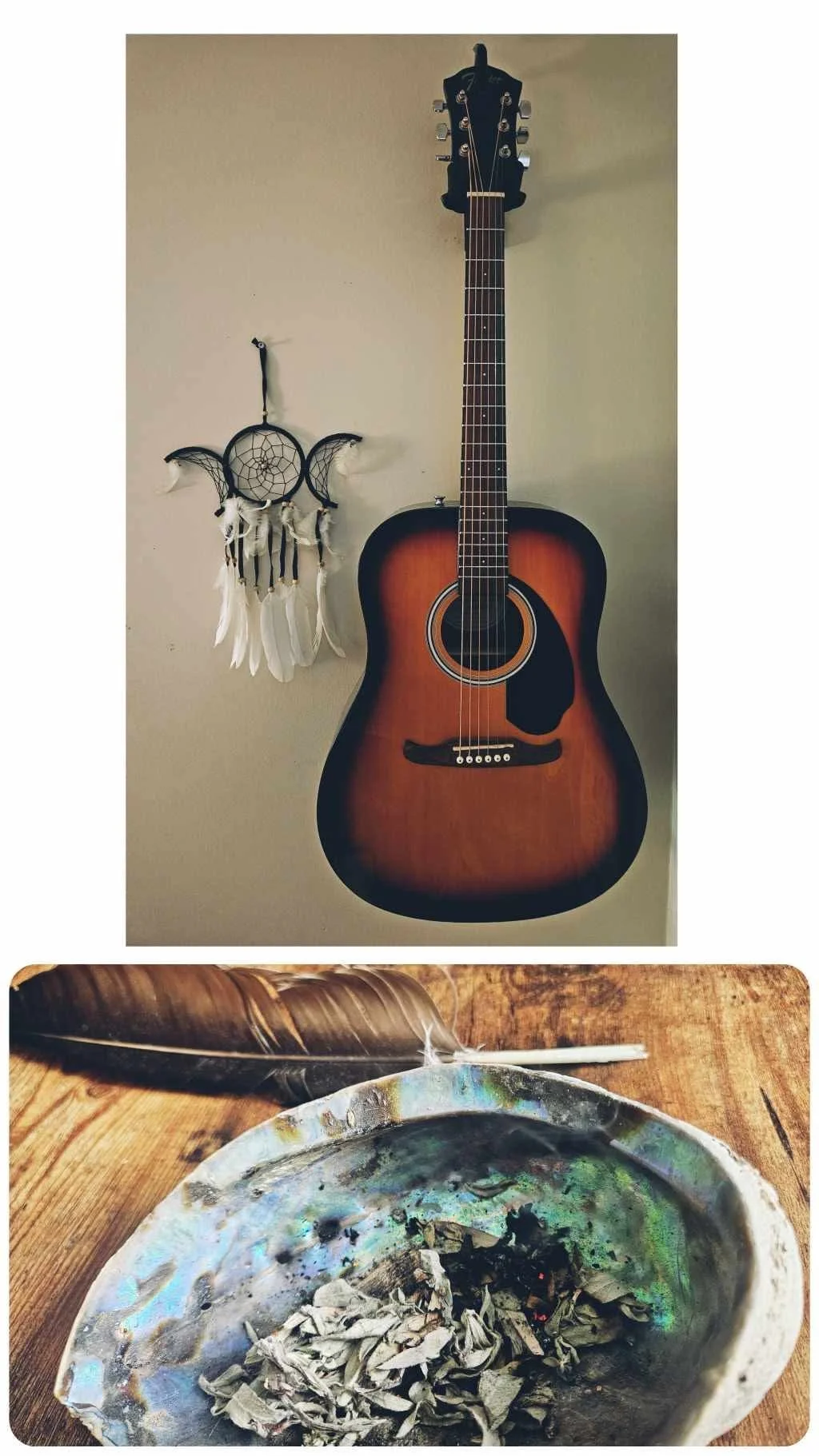

By Tori Sinclair. In my photos on Indigenous perspectives on identity I use the medicine wheel as my guide. Each section represents a different aspect of who I am, and I’ve chosen photos that really reflect my journey. Starting with the spiritual side, I have a photo of my guitar and my smudge bowl. This captures how music has been a huge part of my life, especially during tough times when I was trying to figure out my identity. As I learned more about Indigenous medicines and healing, I found a deeper connection to my roots and spirituality. The music reflects the times I felt lost and how no matter what music is what kept a piece of identity that was always there even through the times I didn't know who I was during growing.

By Tori Sinclair. For the physical aspect, I included pictures from walks and baseball. Walking has been my way to ground myself, especially when I feel lost. The photo with my kids shows our shared growth and the importance of nurturing our identities together. Sports have also played a big role in connecting me to community and having a sense of belonging.

By Tori Sinclair. In the black section, which focuses on mental well-being, I chose photos from my travels. Being in the north or exploring new places helps me find peace when my mental health needs a break. These moments make me feel at home and allow me to learn about different cultures, which broadens my perspective on the world.

By Tori Sinclair. Finally, for my emotional identity, I picked images of the northern lights and an eagle. The northern lights remind me of home and the beauty of nature even in the dark, while the eagle symbolizes love and the importance of breaking generational traumas by fostering love for myself, my family, and my community. All these elements come together to paint a holistic picture of my Indigenous identity, showing how each aspect influences and shapes who I am today.